Road Trip: Sipsmith

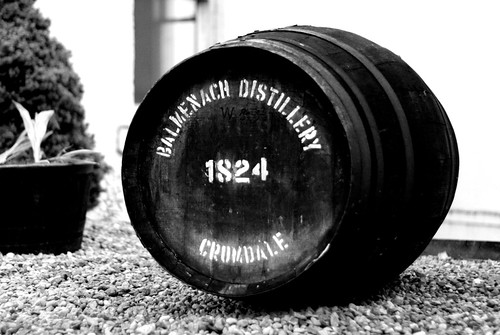

Having lived in Scotland for pretty much all my life, I have a fairly well-developed idea of what a distillery looks like. It would be hidden away at the end of a glen somewhere remote where the taxation officers would be unlikely to stumble across it, with a cluster of copper pot stills in one building and a two-storey-high wooden washbacks for fermentation in another; otherwise it would be a sprawling industrial complex, all 40ft column stills and piping, that would draw comparisons with your choice of near-future urban dystopia.

Distillation, though, is not something that requires a lot of space in itself and that point was well-illustrated when I stopped by an open day at the Sipsmith Distillery in West London during London Cocktail Week.

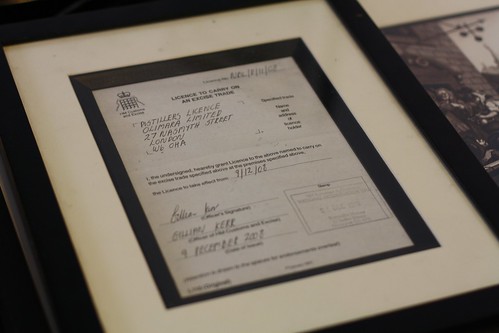

If you didn't know what you were looking for, it would be easy to miss the otherwise unremarkable garage amongst Hammersmith's rows of terraced houses. But the unassuming setting hosts the first new distillery to be granted a licence in London since Beefeater in 1820.

At the heart of the distillery - even though she's located at the back of the room - is another rarity. Where many new products are made either under licence or in second-hand or recycled stills, Sipsmith's range is produced in a new copper pot still. Dubbed Prudence, the still was created by CARL, Germany's oldest still manufacturer, and also has small column attachment - through which Sipsmith's English barley vodka is passed - and a Carterhead attachment which has apparently been used for experiments in flavouring vodka.

One of the upsides of a micro-distillery is that the tour doesn't take too long and our group (of six people from anywhere between Manchester and Japan) spent a large chunk of the afternoon tasting the range with Sipsmith's James Grundy. Their London Dry gin and English barley vodka are fairly well known (partly thanks to the involvement of drinks historian Jared Brown, I suspect), but they've recently expanded into liqueurs with a sloe gin and a damson vodka - the interesting aspect of the latter two is they seem much less sweet than liqueurs of that type generally are which lets the base spirit come through more, particularly in the sloe gin.

Sipsmith are an almost perfect definition of the kind of operation craft bartenders fall for. They're not pushing the boundaries of spirit production, but I get the sense that, for now, they're not inclined to do that. It's a range of artisanal spirits produced by people with a clear passion for both the process and the products they create and it's hard not to like that outlook.